I

Here, in the kingdom of Elgin, over which the sun barely sets, peace reigns as it has done for much of my life. I reckon this to be close to sixty-three years. Even as a boy I was drawn to measurement and first calculated my age at five, and have continued the practice into manhood. Throughout this time I have witnessed calm and suffered none of the hardships of my father. Like many I attribute this to the presence of the stranger.

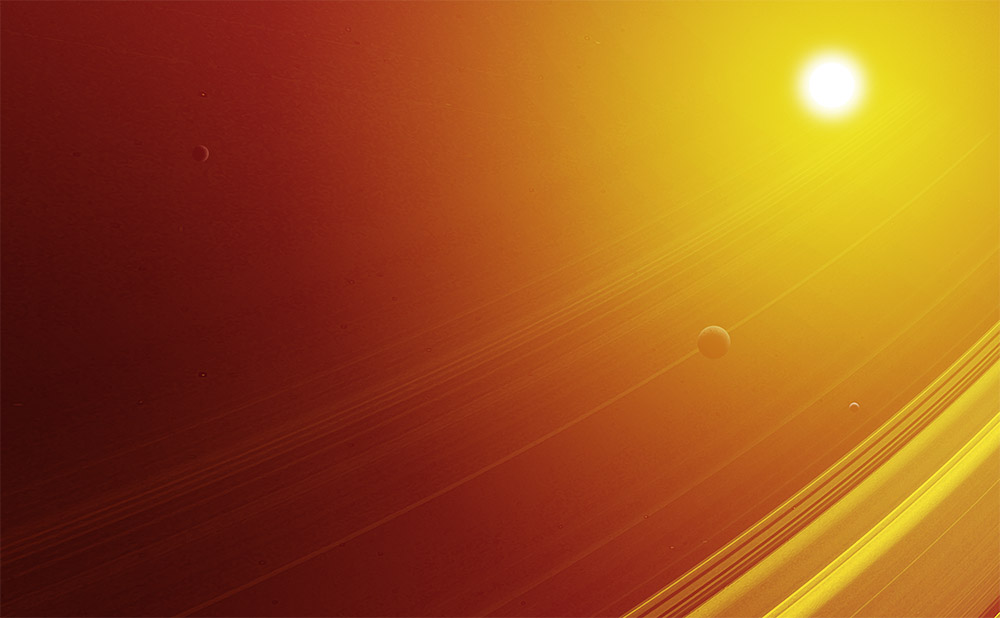

He appeared without pomp in the reign of Cedwyn, the old king, in the year the comet appeared in the sky and when the great planet of Prospero loomed largest in the sky during its long circuit, its rings said to have been visible even during the day in the north. Arriving at court he demanded an audience with the king, which was granted, some saying his outlandish appearance speeding his route to stand before the court, foreigners being then a rare sight in the kingdom.

It is written he demanded to fight the king’s champion, a challenge open to all men regardless of rank. Then as now the tradition of selected champions fighting in the stead of armies to determine victory was long established. Some tried their hand and few lived to vanquish the king’s man. But everyone agrees the stranger demanded just this. The chancellor, believing the stranger ignorant of our customs, was said to have humoured him. It is said the king himself intervened, keen to see how his champion would avail himself against such a giant of a man.

Soon thereafter the court assembled near the armoury. This was only the second time it had done so during the old king’s reign, all other champions having risen through the ranks unchallenged, appointed as a result of their martial proficiency. Aldermen came from around the land of the Nebo to witness the rare event.

The stranger, adorned in the light armour of a foreign land, drew his strange curved sword. It is said the crowd laughed when they at first saw the instrument, puny in comparison to himself and his opponent who wielded the claymore common to the clans of the north. Unlike the traditional armour and the bulk of the champion, the thin blade, that observers swore could be managed with a single hand, looked to be no match. Indeed, it is believed the weapon was deliberately blunted along one edge.

Macrory, the king’s man, was said to have lunged only half heartedly. Although the champion, and the vanquisher of the Powells only four years previously, he was known to be a kind man, attributing his success to the stature given to him by God and not through a yearning for violence. Intending to merely disarm the stranger and, with the king’s blessing, show charity, it is said he swung with his blade twisted so as to daze the challenger but not kill. Witnesses described the movement of the stranger as swift, so swift the main chronicler of the event, the bishop of the Nebo no less, believed him to be infused with the Holy Ghost. Several blows were attempted by Macrory, each more severe than the last, but none found their mark. Then, the stranger’s light blade moving too swiftly to see according to witnesses, Macrory’s own weapon was knocked from his hand and he ended on his knees with the stranger behind him, the sharpened edge of the sword at the champion’s neck. There he paused and sought the king’s decision. Tradition dictated one must die but the stranger, already having succeeded in securing an audience and a contest in a single day, further abandoned the traditions of the Nebo and asked for clemency for the champion. Even he, a foreigner, had heard of the man’s service to the kingdom and stated he would be honoured if the king would grant him this wish.

Naturally Cedwyn did so. Macrory, the champion, was defeated. Tradition mandated the victor become the new champion, but no one had imagined a foreigner would assume the post. Yet the rules were clear. The stranger offered his services and the assembly retired from the field.

Within a week the king accepted the stranger’s offer. Having witnessed himself the man’s speed and skill the king, eager to secure his borders, planned to take him on campaign. Some say he joined Cedwyn on a hunt, further demonstrating his accomplishments with a range of weapons, including the pike commonly used to hunt bearpig. Others claim this an invention, and the king initially spurned the stranger’s offer and only conceded after he fought several men. Macdougal implies the queen, then still young, was much taken with this foreigner, herself a stranger at court. Whatever the truth the stranger became the new champion and word of his appointment soon spread.

Rumour, which persists to this day, long after these events, had it that the man’s face was never shown, an exaggeration. His unusual garb, said to resemble more the garments of a monk or even a woman, was a source of gossip from the earliest days. Similarly, his face coverings, said to be common in the far south, were a novelty here in the land of the Nebo. It is my own view that the face covering — little more than material covering the head, a necessity in the deserts of the south — conjured up a fancy in the minds of the court ladies, their propensity for gossip ensuring the stranger’s legend was established in haste. Macdougal, the king’s own chronicler, makes no mention of the fact. And while Cedwyn’s detractors draw attention to this as a conspiracy of silence it seems more likely to me to be the imaginings of women rather than fact, perpetuated even in these times when many young women have been unwisely admitted to the schools run by the merchant class, educated beyond the abilities of their sex.

Within the year of his appearance the old king’s troubles with the Powells resumed despite them swearing oaths only five years before. The chronicles tell of cattle raids to the west and there was talk of the younger Powell, said by many to have been unhappy with the peace, stirring up trouble. Having settled matters less than five years previously the unhappy king called together his councilmen. Most sued for peace, with none suggesting war. It was around then that the older Powell died in mysterious circumstances. Poison was suspected. Further suspicion fell on the old king. Although the incident did not lead to war some suspected the stranger was as much assassin as champion. Others yet insisted the younger Powell did the deed, having never seen eye to eye with his uncle.

The two soon met on the field, the old king’s army made up of a thousand regulars and twice as many from the realm. The Powells were reckoned at twice the number, but only a few score the aldermen’s men. They were then keen not to fight and a match of champions was proposed. The Powells’ man, a veteran of his uncle’s campaigns, and known to be skilled in man-to-man fighting, was brought forth. The king introduced his champion, the stranger. The chronicles clearly state he was without armour, draping himself only in his effeminate clothes, said to be leggings made from a womanly material, although some also claim cow hide, and his head covering obscuring the face. Armed with his light sword he stood before the Powell champion. Although he had height, the Powell man was said to be bigger. Wielding a claymore he swung at the foreigner, who moved quickly, like a smaller man, although his lack of armour gave him the advantage in speed. It proved decisive as the bigger man quickly tired. After some minutes, each army looking on with their nobles, the stranger moved quickly and disarmed the other then with swiftness took the head off his opponent. It is said his bulk stood for a full minute before toppling to the mud.

The old king was jubilant. This was now the second victory over the Powells, fairly won by a champion. The rabble who made up the bulk of his contingent made to leave before the negotiations had even begun. This breach in protocol enraged the younger Powell, although the king in his wisdom intervened. These were farming men with fields to tend. This won him the admiration of the peasants, an event still talked of today. But it put murder in the heart of the younger Powell. Consumed with hatred at his fair defeat he called a council with his aldermen. None have recorded the goings on but the result was plain. The aldermen murdered the younger Powell. Macbeth the monk concluded at the time the younger Powell wished to attack the old king, despite the rules being clear. Cedwyn treated the vanquished with fairness, and had made clear his desire for Powell and his men to retain their lands. But some men covet more than is wise and the Powell aldermen solved the problem. They left the required number of hostages and made for their own realm. Peace descended onto the plains, the old king wise enough to let the Powells be.

Around the time of the victory over the Powells Elgin was born to Cedwyn. The queen had been barren and had not produced a son. The bishop’s private journals warned of the need to find another wife for the king should the queen fail to perform her duty, her being already the old king’s third wife. Prior to this the bishop’s journals betray some troubles over the queen’s closeness to the stranger affecting her duty. He thought the king to be inattentive to the matter, awed by the stranger’s prowess on the hunt. But the bishop’s growing animosity towards the stranger perverted his judgment. No mention is made of this after the birth of Elgin and some attribute this to the nature of the bishop himself, said to have been a covetous man prone to envy. It is my own view this was the beginnings of suspicion by the churchmen on the motives of the king’s celebrated champion, a prescient emphasis with the Church being the governors of tradition the stranger himself would eventually do so much to disrupt.

The kingdom rejoiced at the news of an heir. The old king sent messengers throughout the land. The Mackays in the east killed the king’s messenger and sent back his head. A warning since word of the Powells had reached them. Calling his council the old king marched eastward.

The army met the Mackays at Fraserburgh. Mackay had raised a force of three thousand men. The old king had less than two thousand. Cedwyn proposed a meeting of champions and the Mackays agreed. The stranger went forth and met the Mackay champion, a man unbeaten in all bouts. The stranger felled him with a single stroke, removing the head. But the Mackays refused to observe the protocols and attacked that night before the negotiation. The king’s army were dispersed with more than half the men slaughtered.

The stranger, hiding in the mountains with a small group, made his way back to the Mackay’s position near the sea at Fraserburgh. His men, less than fifty, waited while he entered the enemy’s camp disguised as a trader. Jubilant at their victory the stranger made his way to the chief’s tent and singlehandedly slew Mackay and his companions. Eleven aldermen of the Mackays were also killed at this time. It was morning before the alarm was raised. The chronicles state the king was by then fifty miles to the west but the stranger made his way to the old king’s position in time to reverse the rout. This is unlikely but is not contradicted by Macdougal. It seems to me this event was written later, perhaps by Macdougal’s acolytes after his death, their ignorance of the north apparent, them being the product of the new schools founded by the merchants. I have walked the road to Fraserburgh and can attest its length of more than fifty miles. It would take a man on horseback several days even now with the roads built there by the Westerners. In these earlier times, accounted above, it is not likely the stranger could span the distance on foot in only a single night.

All the accounts agree the old king rallied his remaining men and marched on Fraserburgh to again confront the Mackay army. Three of their aldermen led the men. But Cedwyn gained the victory and slew their entire army with none left alive, not even the young. The Mackays, still lying in their tents, were refused a Christian burial and their bodies thrown into the sea with their attendants.

Nothing else of the incident is mentioned in the chronicles, but Macdougal’s private journal mentions a doubtful episode. Macdougal, who was himself present at the Mackay’s camp, noted the manner of the death of the leading men. Each had a small puncture in the forehead. This, he claimed, was missed by others, the wounds obscured by blood, by then blackened and thickened due to this being some time after their slaying. Macdougal inspected several of the corpses and wrote that each had the puncture, with the back of the head destroyed, as if each man had received a strong blow from a weapon like a hammer. These unusual marks of death are absent from all other accounts.

While an educated man, Macdougal was the son of a noble and educated by private tutorship, his self-appointed role of chronicler and scribe a result of his station rather than long study as with the traditional churchman. In this he was a precursor of the new generation of dilettantes, in many ways the prelude to the southern philistines who imagine themselves scribes because they wrestle crudely with the divine gift of composition in the production of fabricated tales for the imbecilic multitude. It is well known Macdougal declined in later years. Some have speculated he contracted the southern pox as a result of whoring in his youth, a practice common with his class even now. His journals, although a wealth of information on these times, contain some fancy that could be an early sign of the fantasms that can assault a man’s mind when the pox takes hold. When I first met Macdougal as a youth he was already on his way to becoming a simpleton. I believe the church-trained chronicler has to tread warily when using the man as a source. He mentions nothing else of the incident and I include it here only to establish the unreliability of his proclamations.

The king then marched further north to the place of the Mackays at the sea and laid waste. At the fortified city of Rora the army broke down the walls and put the people to flight.

At this time ships came to Nebo and besieged the city. An army from the south had known of the old king’s movements although they failed to take the city. When Cedwyn returned he called his councilmen and resolved to march south. Macdougal states the stranger advised against this, calling instead for them to wait until the spring.

Through winter the old king received messengers from throughout the north. Word had spread of the victory at Fraserburgh and the movement of peoples unsettled the aldermen. The old king dispatched the stranger with sixty men to secure the roads. They made their way to Rora by ship and the stranger urged the townsfolk to return to their former city. With no leading men the stranger convinced them to form a council of their own. It is said many at court were angry at this innovation, since it is known the people cannot govern themselves.

The chronicles mention the stranger making peace with the Steel Bird cultists known to inhabit the area. These were further north and, despite their heresy, had been left in peace by the Mackays. It is understood they tolerated them because of their skill in shipbuilding and fishing, and they supplied the Mackays with weapons. The bishop’s man who had accompanied the stranger called for their destruction. The stranger, emboldened by his innovation at Rora, contradicted these orders and sued for peace. The Steel Bird heretics, who hold the pagan belief that man was delivered to the world in the belly of a steel bird, were said to have no leading men and no allegiance to others, not even the Mackays. Nothing else is mentioned in the chronicles although Macdougal states the bishop was angered by the leniency of the stranger and sought to turn the king against him.

The stranger left five of the aldermen at Rora and returned south in time to join the campaign to check the Southerners.

~ ✷ ~

II

At the end of winter word reached the court Southerners had been seen within the kingdom. The alderman Henry was sent south to reconnoiter. Within a month he was routed by a southern army and killed. By this time the Southerners had learned the king was at court and not campaigning in the north and they turned back, eager to avoid conflict.

Cedwyn was keen to reach the south and proposed they march directly. The stranger suggested an alternative route, travelling down the eastern side of the country. The leading men of the kingdom thought this madness, but the old king gave the word. Within only three weeks the stranger’s scouts reported back that they had overtaken the unsuspecting southern army and the king set about creating an ambuscade in the place with the shallow river known as Alford. The southern army marched on, unaware the king’s men lay in ambush. They camped near the riverside, Cedwyn having issued orders that no glims or fires be lit. As evening came on the king’s army attacked the unsuspecting Southerners. Their lead man was killed along with his guard and most were slaughtered. The stranger gave orders to capture one of their men, despite the king’s own order to slaughter them all. This fact is omitted in the chronicles but included in Macdougal’s account. The man, when presented to the king, was sent south to carry word of the old king’s army and his deeds. The leading men were in low spirits because of the stranger’s position, now at the side of the king, and condemned the move. The escaped man would lose them the advantage of surprise.

Yet as the army moved further south every town and city opened their gates to them after the first. It was this first city, named Edzell, where the king tried a novelty. Offering to not sack the city in return for an oath, the citizens agreed. Even their offer, to throw their chief man from the battlements, was rejected, their word enough to secure their protection. The leading men of the time were enraged by this. The alderman Keith left with his charges in protest, but the old king pressed on with his innovation. As is common in peasant communities word travelled faster than the army. The next city, also fortified, sent emissaries which the king welcomed. They were promised protection in return for their oath which they freely gave.

This continued as the army travelled south. A score of towns and cities pledged allegiance and all were left unmolested. The city of Kilrenny was the first to resist. Protected with a deep ditch and a full wall, it was said to be impregnable. As the army camped close by the old king prepared to lay siege. But the town was betrayed before the army could amass. A group of sixty of the king’s men gained entrance, one of them the stranger, and the city fell. The king hanged the leading men but did not sack the city. This again drew the anger of his own aldermen, but he stayed with his plan. The chronicles say little on the matter, but Macdougal insists the stranger himself scaled the walls and admitted the sixty while the city slept. This feat is impossible given the height of the walls is over a hundred feet in places. I have seen Kilrenny myself and can attest to its fortifications and the impossibility of scaling its high walls. The chroniclers no doubt omitted this fancy of Macdougal’s as another example of the fantasms wrought by the pox. They sensibly conclude betrayal as the means of entry.

By the time of the rains that year, which arrive sooner in the south, the old king had conquered over a score of southern cities and laid waste to their army. The contingent made it back to Nebo before winter. It was at this time word came back that many of the cities that had pledged the oath had returned to their southern masters, convinced Cedwyn would not follow through on his promises. By summer, as the king made his way back to the south, it transpired all of the cities were still with Cedwyn. The chronicles mention nothing more of the incident, but Macdougal observes that the stranger was absent throughout winter and spring. Southern monks, recorded by Macdougal, talked of a spectre shadowing the leading cities and of unusual deaths among the leading men. The southern chronicles record the townsfolk as reporting the sight of blinding flashes of light in a number of the cities which they attributed to the presence of the Holy Ghost, although the southern scribe Ashcroft dismisses this as peasant foolishness. One report spoke of a dark man seen in one of the cities, using magic, felling men from a distance of twenty feet or more. For a brief time these rumours gripped the south although Ashcroft claims the Archbishop of the Vesters eventually banned their transmission on pain of death, him no doubt a learned man like Ashcroft and with a keen eye for the indulgences common among simpletons. Unlike today, the south had long kept the work of chronicling to educated churchmen, the sharpness of their discipline apparent in the sobriety of their works. Ashcroft himself was the first Southerner to postulate the existence of the innermost ring around Prospero, imperceptible to the unaided eye, and only confirmed twenty years ago with the aid of the new lensed instrument developed by the Vesters.

More foolishness yet comes from Macdougal’s interpretations of these events. His account for the following year included tales taken from those same peasants as the old king’s men moved south. Once again he mentions an unusual method of death, this time reported by the southern natives dismissed by Ashcroft. According to Macdougal a surgeon in the employ of the local monastery made note of unusual wounds to the head of the corpses with no other signs of violence, as if struck in the forehead with an arrow and the back of the skull destroyed. Ashcroft makes no mention of course, and this is another fancy conjured up by the demons raging in Macdougal, agitating his imagination beyond the realms of sense.

Over the course of the year the going was hard for Cedwyn. The southern realms at this time had no arrangement of allegiance as each of their places stood alone. Instead of aldermen allied to a king or lord, each town and city had a sheriff. In some places these were passed from each man to his son as in the north, in others they changed hands. This made the task a labour for the old king since each stronghold had to be won over. By the end of this year the king added only fourteen cities to the original twenty before winter came upon them.

The chronicles state that the winter was quiet, with no challenges to the old king. But Macdougal explains the aldermen of the kingdom were unhappy at the position the stranger now occupied at the king’s right hand. He had spoken for the court at many of the southern cities when they were too far for the whole army to reach. But they were satisfied when Cedwyn agreed to keep him on a tight leash and their eyes were wide with greed at the thought of the riches yet to come when they conquered the rest of the south.

It is obvious from both the chronicles and Macdougal’s journals that the old king did not control the stranger, but also the leading men of the kingdom as it was then were satiated with their accomplishments in the southern realm. Macdougal claims to have seen no evidence of mutiny, but then again the stranger’s own accomplishments were soon to grow in value.

The following year the king’s army met a southern army in battle near the place of the great loch in the mid south known as Lakeside. Offering to settle matters in a civilized fashion the Southerners had no tradition of fighting champions. They beheaded the king’s messenger, placing his head on a pike at the head of the army. The enraged king readied the army and attacked at dawn. There was much slaughter and the result was inconclusive. Ashcroft the scribe claims the Southerners held the field but Macdougal disputes this. The southern army disbanded, this being their land they knew the safest routes home. The stranger convinced the old king rather than withdraw the plan should be to push forth while the enemy were dispersed. The aldermen argued against this strategy since the campaigning season was over and the aldermen Ivan and Hamish withdrew.

The stranger led the king’s army further south to the stronghold of the Desmonds where he made them an offer of allegiance. This was refused and the army laid siege. After ten days the city was betrayed and the place reduced. The men it was said had been promised booty although the chronicles mention only the divesting of the city of the Desmonds. Of the leading men there was no sign, them having escaped some days before. Macdougal claims the stranger appealed to the men to show restraint, it being important to him to establish good faith with the Southerners as they had done further north. But the men were in a frenzy. Macdougal, who witnessed the event, said even the children were not spared and the stranger was seen in a fugue. Cedwyn soon joined the army and they ended their campaign for that year.

The stranger did not return with the king and the army but instead took a force of five hundred men further south to harry the southern forces. By spring, when word reached the court in Nebo, he had won over a further eight cities and had drawn up an alliance with one of the southern clans known as the Vesters.

When Cedwyn joined the stranger in the south during the next campaigning season he made him general over all the army. The chronicles mention this only in passing. Macdougal recounts the bitter feud it caused among the aldermen. But the men in the army welcomed the news. Of the five hundred the stranger had taken with them all but three had made it back alive. He was said to always share the hardships of the common soldier, at times himself walking on foot. He insisted himself and his captains ate as the soldiery did leading to the novelty of improved rations and meat twice each week. Macdougal comments that at a banquet one of the leading men’s sons chided the stranger that the common soldier ate better than them to which he returned the common soldier worked harder than idle sons. The chronicles make no mention of the incident, but Macdougal’s journal hinted this further alienated him from the aldermen.

Macdougal also recounts a tale he heard of the stranger’s travels over winter. At one of the fortified towns they encountered resistance, a place with the name of Heacham. The men there used the longbow weapon sometimes used by hunters here in the north, although never for battle, it being an effeminate instrument only fit for cowards. Macdougal claims the men of Heacham dipped the tips of their arrows in poison, a fact known to many far and wide, ensuring few dared challenge them at their town. This fact was unknown to the stranger when he encountered them. Him and two others approached the locked gate on horseback to ask for fealty as was their custom. Macdougal claims all three were penetrated by an arrow each shot from the battlements as were their mounts. As the three retreated, the horses panicking, two of the beasts collapsed and died. The three men were dragged away and taken to safety. That night both the strangers’ companions died in agony, the poison apparent and confirmed by the surgeon. Only the stranger survived. It was said he had a fever through the night but rallied by noon the following day, and was on horseback the day after. The surgeon reported the speed with which the wound scarred over and the lack of puss in contrast to the two dead men. While I am inclined to question much reported by Macdougal, his pox-addled brain playing tricks, this rumour of the stranger is well attested from other sources, both here and in the south. This is the only known account of illness suffered by the stranger, a record matched only by the king, Elgin.

Meeting at the place of the Vesters during the campaign season, the old king returned south with more men, the numbers swelled by the promise of riches. The stranger was now general of six thousand. Few aldermen returned with the king leading to a further novelty. The stranger chose men from the ranks to act as lieutenants. These would each be in charge of a hundred men, with captains in charge of the lieutenants. When the leading families refused, insisting the stranger be replaced, Cedwyn dismissed them all. No further mention is made in the chronicles, but Macdougal states the stranger then appointed captains from the ranks of the lieutenants. These he insisted learn to read and write, itself an innovation. The standard practice now of written orders was introduced then on the southern campaign.

Pushing further south the army at first met little resistance. It is known from Ashcroft the scribe’s writings that the Southerners had learned of the innovations in the old king’s army and looked upon the Northerners with scorn, believing their king to be weak. The first clash seemed to prove them right, with the field held by the southern army, less than half the size of the old king’s force. But there was much dissension in the southern nation among themselves; they had deposed their king Wilbert and replaced him with an imposter to the throne and anyway had no system of allegiance on which to build a kingdom. When the stranger regrouped the men he found the southern army in disarray despite their triumph and led the men against them. They won a great victory as the southern army scattered. The leading men offered terms and the stranger accepted on behalf of Cedwyn. Each were required to provide hostages, swearing with solemn oaths to observe the strictest amity. When the old king joined them it was too late to make it back north so this was the first year he fixed his winter quarters in the southern realm.

The Southerners took this as a sign the Northerners meant to dominate their land. With their own king deposed and their leading men fighting for the crown, the old king took his chance to establish his sovereignty over them. The stranger, leading the army in winter, invested seven of their cities, all of them falling without fight. Ashcroft the scribe, who was resident in Fenwick, observed the siege there himself. The stranger offered terms and they accepted. Leaving only a few men he carried on south.

It is known Ashcroft the scribe was present at the incident at the river which took place shortly after in spring. Although the chronicles make no mention, and Macdougal dismisses it as fancy, the following was said to have transpired. The stranger led his men to a place where a southern army was gathered. Finding them camped openly, there was a strong river between the two camps. As each army faced off it became the custom of the southern army’s leading men to ride down to the river and taunt the Northerners. Ashcroft claims many of the taunts were aimed at the stranger himself, the leading men having learned of his effeminate clothing and his dark skin which they compared to that of the common labourer. While a group of sheriffs stood on the river bank the stranger leapt from his horse and dived into the river. Believing him to have forfeited his life the Southerners laughed. The stranger soon surfaced, half way across the river. He then propelled himself to the other side to the amazement of all. A group of Northerners looked on. The southern group, still believing themselves to be in no danger, were made up of most of the leading sheriffs and their guard. Making his way on to the opposite bank the stranger stood alone. He then proceeded to slaughter every last man, including the guards. Ashcroft says he was armed only with his light sword and wore no armour. He was said to have moved quickly, too quickly for the assembly to react and the event was so swift that no alarm was raised. It took half a day for the southern army to notice. By then the northern scouts had found a shallow crossing and the stranger led them across. The battle was won with the northern army holding the field when the southern army ran in disarray. Within days the stranger received emissaries from the sheriffs in the area, each promising obedience which he accepted.

At this time word was received that the old king was taken ill and he made his way back to Nebo. The stranger was left to control the army. He made yet another innovation by incorporating southern men into the ranks. Even the chronicles take note of the fact this alienated the last of the aldermen. These fought alongside the regular army and the stranger appointed lieutenants and captains from among them. Ashcroft notes the stranger was proficient in the southern tongue.

Over the next seven years the army grew in size, with each of the southern towns and cities coming over to the old king. The chronicles are spare on this period, the northern scribes having returned with Cedwyn to Nebo. Even Macdougal’s journals contain only rumour. Ashcroft the scribe died in the third year of the campaign and was only rarely present, with much of his writing gleaned from southern men after events.

The army became famous for its speed. The stranger split the army into two, with a vanguard of between five hundred and a thousand men, all of them the fastest troops. This vanguard ranged widely across the southern realm with place after place coming over to the old king. In seven years he was absent from the court and the army conquered all of the south. Only the western area, at that time believed to be populated with wild, uncivilized tribes, remained out of the reach of the army. At the beginning of the campaign season on the seventh year word reached the stranger that the old king had departed this life. He was fifty-six. The stranger took off for the court in the north with a hundred of his best men.

~ ✷ ~

III

Elgin, the old king’s son, had seen twelve winters by the time the stranger arrived at Nebo. The chronicles state the boy was protected by a cousin of the queen, and a council of elders to rule in his stead. No mention is made of the stranger, only that the council was suddenly abolished. Macdougal notes the council refused to recognize the efforts of the stranger and sought to alienate the boy Elgin from him. But his mother exerted much influence at court, the council seeing fit to banish her to another town, a decision overturned when the stranger arrived.

Elgin, although only a youth, stood taller than his father and took after his mother in looks. By thirteen he had shown proficiency in all the martial disciplines and in reading, writing and the other arts, his tutors claiming him wise beyond his years. Even at this age it was clear he was not his father’s son. He was slow to anger and less inclined to the hunt. Keen to go on campaign the old king had planned to let him join the stranger in the south when he had seen fifteen winters.

Before that the western tribes made raids into the kingdom. Word reached the court that their crops had failed, encouraging them to travel east. The chronicles state the stranger was despatched with a body of five hundred men to confirm the stories.

The stranger met a caravan of Westerners some sixty miles inside the kingdom, fighting men travelling with families. The chronicles note they claimed indeed to be fleeing starvation. The stranger made peace with them and offered them land to the north. This angered many at court although the move was seen as shrewd by some. By then great riches had been sent to Nebo from the southern realms and the aldermen lived in comfort. Few were keen to go on campaign as their fathers’ had done. Macdougal notes the stranger took few men from the leading families, even relying on southern scouts as they were skilled horsemen.

Returning to court the young king’s guardian, the queen’s cousin, quickly ratified the stranger’s decision. All was well for two years until news arrived of trouble in the north. The Westerners were not a people used to farming. It is said they hunted game when in the west and planted few crops. Scouts reported back they were raiding farms far in the north, all of them loyal to the king.

The stranger left with a thousand men taking the young Elgin with him for the first time. Word soon reached them that the northern town of Baddon had been raided by the Westerners. The stranger insisted Elgin stay at the fortified city of Fornham while he rode on with eight hundred men.

Reaching the town, the stranger found it razed and the townsfolk absent. The chronicles state the Westerners came on to the town and scattered the people. Scouts were sent to locate the Westerners but no sign was found of them. Word came back that they had moved further south. The stranger took the men back and they arrived at Fornham to find the town invested by the men from the west. They had strengthened the town’s defences, building upon the existing walls and trenches. The stranger sent for their leading men but they refused, claiming they had a right to occupancy because of their poverty. The young king, Elgin, had escaped with a guard and was found safe nearby.

The stranger arranged to siege the town, arraying the men around the city. On the third night the stranger himself gained entry, scaling the walls unseen. Armed only with his sword and dagger he killed the leading Westerners and returned Fornham’s men to power. The chronicles only record these basic facts, the town soon returning to normality. But I myself, a native of Fornham, witnessed the stranger firsthand at this very siege. His skill with weapons is well attested here and elsewhere, but what I witnessed there defies understanding. His speed was inhuman, almost impossible to see as he wielded his strange sword. I watched him fell three Westerners, all of them young men skilled in swordsmanship. They attacked him together and were dead in a moment, two beheaded in a single stroke. His height, matched only by Elgin, gave him the advantage, but the accounts of him moving in the manner of a smaller man were true. His foreign clothing marked him out as he moved through the town as did his dark skin and he was soon lost to me, but I had little doubt who I was seeing despite his face partially covered in its obscuring fabric.

As the Westerners proved difficult to settle, their urge to wander driving them through many homelands, the king embraced a novelty, now taken for granted by the young. In those days the court used messengers to take correspondence within the kingdom. The king offered to settle the Westerners across his realm in return for them becoming the king’s messengers. Within five years they had created a berth in many towns, even in the deep south. Speaking their own language, incomprehensible to the civilized, helped create a latticework of protected roads that spread everywhere. Correspondence from the court in the north could now reach the furthest reaches of the kingdom in only weeks. The Westerners became rich on the back of this innovation, encouraging them to establish roots, solving all problems at once.

The Westerners were behind the drive to build permanent roads uniting the kingdom. As owners of these roads they charged tolls for merchants who made the most of the peace. This group too grew rich, with many now richer than the aldermen who were allied to the old king and the southern sheriffs. These same merchants, at the insistence of the stranger, provided the taxes and duties that paid for the establishment of the places of learning, a function now ran by the guild of tutors rather than the Church.

This was only the beginning of the Church’s woes. Once at the very heart of the court, it was rumoured the stranger helped turn the king against them while he was still a young man. Their great store of apothecarial knowledge, once seen as a symbol of the clergy’s mastery of natural philosophy, became the basis for the great hospitals now found at every major town. Cleverly, the king, urged no doubt by the stranger, who I suspect never forgave the clergymen he met on campaign for their exhortation to destroy pagan beliefs, funded these places of healing. As the clergy enjoyed their new status as great healers, so the important task of educating the bright slipped from their hands. Indeed, the young now think of priests as healers rather than learned men, a situation exacerbated by the lust for glory in the clergy itself, with many of the younger clergymen — educated as they were in the inferior secular places of learning — driven by profit almost as much as the merchant class.

With the decline of the Church and rise of the merchant class came a relative decline in the aldermen. The stranger’s innovation in the north, of the peasant folk forming a council without leaders, spread south first, them having no strong tradition of fealty to a king. By the time of the king’s fortieth winter they had made an appearance in the north, much to the disquiet of the remaining aldermen. But with the weak character of the new places of learning, stressing as they did the need to teach all boys and even some girls, a new sense of destiny has gripped even the meanest of peasants. This delusion has yet to run its course, but it cannot end well.

As commerce grew so warfare declined, and the stranger retreated more into the background. He was rarely seen at court and when the king’s mother moved permanently to a town some miles away it was said the stranger accompanied her. But his hand can be seen everywhere. As the peace spread when the Westerner’s roads penetrated into every corner of the kingdom so did the pace of innovation. The application of apothecarial knowledge was just one manner of the whole. Word is forever reaching me of novelties even from the furthest reaches of Elgin’s kingdom. There is talk of the blacksmith of the Vesters in the deep south having built a great wheel that rests in the river Vester itself, driving the threshing paddles in a mill, although this is an obvious fancy conjured up in the minds of the young and the peasant folk, unaccustomed as they are to the rigours of mental discipline. The spirit of Macdougal lives on.

Despite the benefits ushered in since the appearance of the old king’s champion there are dangers to this pace of change. The imaginings of the peasant folk are one example, but the minds of the undisciplined, especially simpletons, are unaccustomed to change, fired up as they are with false confidence imbibed from their unneeded schooling.

This is evidenced by the fate of the Steel Bird cultists. They survived at the stronghold in the north. Their precarious position serving the Mackays, and their lenient treatment at the hands of the stranger himself, ensured they survived. By the time of the rise of the merchant class they began to flourish, their facility for the working of machines soon exploited by those lusting after profit. Building great ships that could traverse the oceans faster than caravans could travel made their skills see demand. Their heretical views, first overlooked by the stranger, were equally ignored by the merchants, a class not known for their piety. As a consequence some of their damnable heresies found their way south where they established themselves in the manufacture of practical machines, the most famous of them the water pipes that now feed many of the southern cities, that land having long seen parched summers unlike the more civilized north. The king, a patient man, has long overlooked the influence of the Steel Bird cult, a rare example of shortsightedness on his part due, I have no doubt, to the influence of both his mother and the stranger.

And what of him? He was always there. Or so it seemed. He was rarely witnessed after the wider kingdom became established. Now with the king a mature man some question whether he ever existed. I know he did, having seen him with my eyes at my own town of Fornham. But the question, often murmured nowadays, is the wrong one. It would be fairer to ask how many strangers the royal family have employed. When I first saw the man all those years ago in Fornham, when I myself was a youth, he was himself no older than thirty-five. My fleeting glimpse of his distinctive face showed a man of that age, in his prime. I saw his face only once more many years later when I became a scribe at Elgin’s court. It was definitely him, his height always marking him out from others along with his unusual garb and dark skin. Walking to the queen’s garden I caught a glimpse of the man, who looked the same in every respect, his face retaining its youth. This impossibility can only be explained if the stranger was more than one man, which was perhaps the real reason he was so often invisible and his face covered even in public.

The true danger of our society, where weak minds can now meet novelty without the guiding hand of the wise, is nowhere better seen in the rumours of the queen. By the time she was old, now ten years past, she took a pilgrimage to the shrine in the deep north. As is now widely known she was lost when an uncommonly cold winter came upon them. What is less known is that the stranger accompanied her. This was in the year of the minor comet, seen by the northern towns. Although the kingdom believes the stranger to be still present he is in fact absent.

In the furthest reaches of the kingdom, both north and south, rumours circulate, their subject often the great lady herself. Minstrels openly sing of the fate of the queen and the stranger, with many claiming to meet them on their travels. Ballads abound of meeting a pale beauty with flame-coloured hair, accompanied by a tall, dark man, both of them youths not long past the first flush. These indulgences are to be expected when we destroy tradition and elevate the limited beyond their means. As is the way with such things, merchants and others afflicted with commercial ambition have not been slow to exploit this foolishness. In the south, where the once noble art of chronicling events revealed through the divine gift of the written word has become corrupted to encourage the production of indecent tales in printed form. Philistines of dubious skill write of northern conspiracies with the Steel Bird cultists, their magical skills including the secret of eternal youth.

The peasant folk, even those in the far south, believe she was taken to heaven in the belly of a steel bird, raised from the dead to walk among us, a blasphemous corruption of the gospel of the Risen Christ. This damnable aberration has taken seed everywhere in the kingdom, and is known even to the king. And this is the real legacy of the old king’s champion, the erosion of discipline in those with little enough discipline to erode. We have him to thank for the peace that has reigned for much of my life, but the kingdom has paid its price.

✷ ✷ ✷

©2021. All rights reserved.

Image: gdoc.